Key Texts: Carmichael, M. (A. C.). (1834). Domestic manners and social condition of the white, coloured, and Negro population of the West Indies.

This primary source looks at this text’s relationship between this text, song, carnival, rebellion, and resistance. One of the ways this section does this is through its focus on hierarchy and small acts of defiance.

The small portion of Mrs. Carmichael’s journal that refers to Carnival is critical in depicting Carnival’s relationship with rebellion and resilience. Her journal highlights the power dynamic through small acts of defiance, shown in the way West Indian people are able to preserve their culture through rituals of dance, song, masquerade, regardless of the enslavers' attempts to rid them of it.

Caption: These are the contents pages of Mrs. Carmichael’s journals.

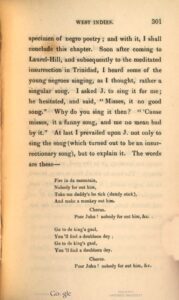

In her journal, Mrs. Carmichael refers to a canboulay song she heard enslaved people singing. When referring to the songs, she writes: “At last, I prevailed upon J. not only to sing the song (which turned out to be an insurrectionary song), but to explain it [..] Take me daddy’s bo tick (daddy stick) and make a monkey out of him [...] the explanation of this song is, that when the bad negros wanted to do evil, they made for a sign, a fire on the hill-sides to burn down cane” (Carmichael 1779, 301-302). The song being referred to is known as a canboulay song (Hollis Liverpool), and people “coded” the song being sung, so enslavers would fail to recognize its true meaning. The song represented cane burning and was sung to reclaim power against colonizers through its use of coded language and ideals of resilience. Colonizers wanted enslaved people to forget or forgo their culture, but instead, enslaved people used their cultural traditions in order to regain power through their opposition to colonizers.

Caption for transcription below: These are transcriptions from a section of Mrs. Carmichael’s journals where she looks at Canboulay songs.

Specimen of negro poetry; and with it I shall

conclude this chapter. Soon after coming to

Laurel-Hill, and subsequently to the mediated

insurrection in Trinidad, I head some of the

young negros singing, as I thought, rather a

singualr song. I asked J. to sing it for me;

he hesitated, and said, “Misses, it no good

Song.” Why do you sing it then? “‘ Cause

Misses, it a funny song, and me no mean bad

By it.” At last I prevailed upon J. not only to

sing the song (which turned out to be an isur-

rectionary song), but to explain it. The words

Are these--

Fire in da mountain,

Nobody for out him,

Take me daddy’s bo tick (daddy sticks),

And make a monkey out him.

Chorus.

Poor John! Nobody out him,

Go to de king’s gaol,

You’ll find a doubloon dey;

Go to de king’s gaol,

You’ll find a doublon dey.

Chorus.

Poor John! Nobody out him,

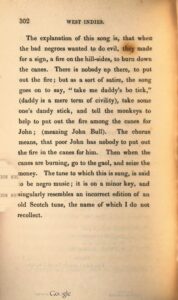

302 West Indies

The explanation of this song is, that when,

the bad negroes wanted to do evil, the made

For a sign, a fire on the hill-sides, to burn down

The canes. There is nobody up there, to put

Out the fire; but as a sort of satire, the song

goes on to say, “take me daddy’d bo tick,”

(daddy is a mere term of civility), take some

One’s dandy stick, and tell the monekets to

Help put out the fire among the canes for

John; (meaning John Bull). The chorus

Means, that poor John has nobody to put out

the fire in the canes for him. The when the

Canes are burning, go to the goal, and seize the

money The tune to which this is sung, is said

To be negro music; it is on a minor key, and

Singularly resembles an incorrect edition of an

Old Scotch tune, the name of which I do not

recollect

Caption: These are actual screenshots of the text translated above from Mrs. Carmichael’s journal.

By singing these songs, enslaved people were actively rebelling against the systems that oppressed them. This resistance represented a sense of release that empowered the enslaved, giving hope that one-day freedom would come. Although enslaved people were living within systems of enslavement constantly dealing with emotional, mental, and physical exhaustion, abuse, and attempted erasure of their culture, the enslaved were not allowing colonizers to control their minds nor connection to their culture. By singing songs of resistance, enslaved people were challenging colonial power in a way that rejected the need for acknowledgment by their enslavers, hence giving enslaved people a sense of control. These songs also depict the exclusiveness of these acts of defiance. Before the song was explained, Mrs. Carmichael had no idea of the significance these rituals carried, merely shocked to hear the song was an “insurrectionary song.” Even after the coded language was explained, there appeared to be a distinct lack of understanding or acknowledgment of the complexity these songs carried. In “Origins of Rituals and Customs in the Trinidad Carnival: African or European?” Hollis Liverpool refers to the song, claiming “Mrs. Carmichael testifies to many truths: enslaved Africans used to deliberately set fires to the canes; they had an offstage life of satire, rebellion, and resistance; many African melodies survived the Atlantic crossing to become part of the musical armory of New World Africans” (Liverpool 1998, 32). This text speaks to the critical role rebellion plays in maintaining culture as well as stresses colonial incapacity to understand the significance of these rituals. The text not only depicts a key form of “evidence” regarding the Cannes Bruleescelebration but also gives some insight into the language used.

Works Cited:

Carmichael, Mrs. (A. C.). Domestic Manners And Social Condition of the White, Coloured, And Negro Population of the West Indies. 2d ed. London: Whittaker, 1834.

Liverpool, Hollis Urban. "Origins of Rituals and Customs in the Trinidad Carnival: African or European?" TDR, no. 3 (1998): 24-37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1146677.