Carnival’s Indigneous Origins

This section gives some background information about carnival’s Indigneous origins, progression over time, and ties to rebellion. One of the ways this section does this is through its focus on Cannes Brulees, music, and, carnival’s diaspora identity.

Carnival’s celebration of rebellion against enslavement has roots in both African and Indigenous cultures. Carnival first took shape in the late 18th century on the island of Trinidad and Tobago, emerging in a ritual called Cannes Brulees (French for “sugarcane burning”). Enslaved Africans purposefully set fire to sugar cane intended for sale, resisting plantation slavery through the the destruction of its valuable export commodity--sugar (Liverpool 1998). Instruments resembling drums and sticks were used during Cannes Brulees to perform percussive music linked to the African roots of enslaved people; this music reconnected the performers with their ancestors and the past spirits that guided and sustained them (Liverpool 1998). This musical performance was an act of reclaiming the cultural vitality, taking ownership of their culture and enacting empowerment through these acts of rebellion.

Caption: This is an image of steel pan drums.

Citation: “The Joyful and Riotous Steel Drum.” KCRW, September 11, 2018. https://www.kcrw.com/music/articles/the-joyful-and-riotous-steel-drum.

Cannes Brulees would later become known as Canboulay, which today we call Carnival (Browne 2018). In 1881, the British colonial government tried to ban Canboulay by outlawing its use of sticks and drums, because colonizers deemed these too violent (Batson 2004). However, Afro-Caribbeans fought back resulting in Canboulay Riots (Batson 2004). These new restrictions forced people to find new methods of practicing these rituals through percussion instruments like the steel pan (an instrument resembling a drum that originated in Trinidad), further encapsulating this idea of rebellion

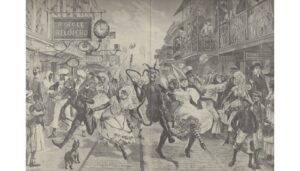

Caption: This is a controversial portrayal of “Carnival in Port of Spain, Trinidad, 1888,” because it is drawn from a colonial standpoint—one that associates devilry and chaos with Carnival yet it offers an early depiction of a colonial performance of Carnival (Browne 2018)

Citation: Prior, Melton. “Carnival in Port of Spain, Trinidad, May 5, 1888,.” The Illustrated London News, 1888.

Songs were also sung during these rituals as a means of speaking to the lived experiences endured as well as a way of retelling stories. Today, many Calypso and Soca songs still carry themes of rebellion, empowerment, and social commentary as well, such as Chalkdust’s “My Way of Protest” (released in 1977), Brother Marvin’s “Jahaji Bhai”(released in 1996), Calypso Rose‘s “Leave Me Alone” (released in 2016), and Machel Montano’s “Famalay” (released in 2019). History manifests itself into the present. After slavery was abolished, people still practiced performance rituals and oral tradition from pre-emancipation rebellions as a means of celebrating their freedom and remembering the past. This celebration today is known as Carnival. Jouvay, marks the beginning of Carnival, taking place very early in the morning, and primarily stems from the emancipation ritual where people would fill the streets. Today, Carnival is an act of celebration for freedom throughout the entire Caribbean and the Caribbean diaspora across the world where people celebrate their culture and remember all the pain that their ancestors endured.

Works Cited:

Batson, Dawn K. ‘Voices of Steel A Historical Perspective’. In Carnival: Culture in Action: the Trinidad

Experience, edited by Riggio, Milla Cozart, 195-205. London: Routledge, 2004.

Browne, Kevin Adonis. High Mas: Carnival and the Poetics of Caribbean Culture. Jackson: University

Press of Mississippi, 2018.

Liverpool, Hollis Urban. "Origins of Rituals and Customs in the Trinidad Carnival: African or

European?" TDR, no. 3 (1998): 24-37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1146677.

Images:

“The Joyful and Riotous Steel Drum.” KCRW, September 11, 2018.

https://www.kcrw.com/music/articles/the-joyful-and-riotous-steel-drum.

Prior, Melton. “Carnival in Port of Spain, Trinidad, May 5, 1888,.” The Illustrated London

News, 1888.

Further Readings:

Guzda, John K. "The Canboulay Riot of 1881: Influence of Free Blacks On Trinidad's Carnival," The

Exposition: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 4.(2012)

Fergus, Claudius. "From Slavery To Black Power: The Enigma Of Africa In The Trinidad Calypso."

Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana, no. 16 (2014): 1-26.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/26512496.

“Keywords for Caribbean Studies.” caribbeandigitalnyc.net. Accessed March 16, 2021.

http://caribbeandigitalnyc.net/keywords/2020/11/21/carnival/.