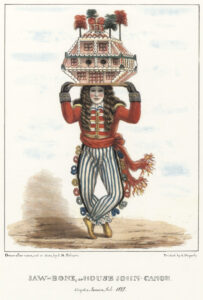

Key Text: “Jaw Bone or House John Canoe” and Koo Koo or Actor Boy published in 1837/1838

This primary source looks at the relationship between carnival and the festival of Jánkúnu.One of the ways this section does this is through its focus on masking and its ties spirituality and rebellion.

Issac Mendes Belisario, “a Jamaican Artist of Jewish decent,” had a passion for art and some of his art is representative of colonies resisting/going through radical changes (in terms of emancipation and power dynamics). Belisario was born in Jamaica, but moved to London as a child and lived there for much of his life. He returned to Jamaica later on and stayed for around 15 years. Many of the archival documents I reference were drawn or written from the perspective of westerrn colonizers, having the perspective of an Afro-Caribbean person during this time period is extremely important. Although, Belisario lived in London, he has more ownership over this work and these celebrations than native Europeans do.

Jánkúnu oftentimes known as the “Afro-Jamaican masked festival” resembles a branch of Carnival that stems from the Kongo and Akan African roots (Thompson 2007). Like Carnival, Jánkúnu relates not only to masquerade, but performative practices, spirituality, and opposition to the social hierarchy perpetuated in enslavement. Jánkúnu is referenced in this exhibit as it works to show parallels in acts of rebellion across the Caribbean as well as illustrates how nuanced and complex Caribbean culture is. Though, in Jánkúnu, it is important to note the emphasis placed on the connection to “religious veneration” compared to the emphasis of spirituality placed on Carnival (Martinez-Ruiz 2019)

Caption: Koo Koo or Actor Boy” is an image of street performer man in a costume lifting his mask to show his face.

“Jaw Bone or House John Canoe” depicts a person with a small decorated house on their head dancing whereas “Koo Koo or Actor Boy” depicts a street performer with a very elaborate costume. In both images, a mask is used to hide the person’s face. Looking at “Jaw Bone or House John Canoe” and “Koo Koo or Actor Boy” masking is used to “transform” one as both images include a person with a mask/costume doing a performance of some sort. This in part could be used to gain power in a society where Blackness is constantly othered. This depiction is shown in the way the mask is positioned on “Jaw Bone or House John Canoe” compared to “Koo Koo or Actor Boy” where the man reveals his face. In both images, it is important to note that the person is looking directly at the viewer and the body is more or less angled straight up, depicting the power and authority the person carries. The image also depicts the social commentary Belisario was making about class dynamics as highlighted by the crown on top of the miniature house in “Jaw Bone or House John Canoe” as well as the use of wigs in both images. The use of western clothes emphasizes how costume/masking was largely based on the clothes of westerners, as “it was largely impossible to continue with the African tradition of fabric production and design, the continuity of traditional patterns, symbols, and other design elements was made possible through a process of selection, appropriation, and re-functionalization of visual vocabulary available in the colonial context” (Martinez-Ruiz 2019).

Caption: “Jaw Bone or House John Canoe” is an image of a man dressed in red costume with a wig carrying a intricate decorated house on his head.

“Jaw Bone or House John Canoe'' and “Koo Koo or Actor Boy” manages to illustrate the complexity of Caribbean culture by bringing together these nuanced races, genders, and visions of the future (Martinez-Ruiz 2019). As Martinez-Ruiz says, “prints depict the mixing of former slaves and local bourgeoisie with the presence of Afro-Jamaican cultural traditions and indicate a space where former slave, creole, and white cultural expressions were brought together and reconfigured” (Martinez-Ruiz 2019). We could use these ideas to also look at the ways in which Carnival was shaped by European colonization, though Carnival originated from distinctly African practices, the incorporation of colonial clothing and other practices was a result of colonialism. Belisario’s art illustrates the mixing of colonial powers, Africans, and Creole cultural traditions, though, in these paintings, the power is given to the formerly enslaved person, because the enslaved is in control of the way they chose to use/perform these masks.

This text also allows us to look at the many ways Carnival manifests itself on different islands. Caribbean culture is nuanced and complex in the sense that each island is different and carries its own variations of a similar culture. In “Globalization And Trinidad Carnival: Diaspora, Hybridity And Identity In Global Culture”, Nurse argues that Carnival is part of the diaspora culture and it works to create “overseas Caribbean Carnivals” that has added to the Caribbean’s cultural industry (Nurse 2010). As Nurse says, “Carnival as a cultural activity is not just about merriment, colorful pageantry, revelry, and street theatre. Carnival is born out of the struggle of marginalized peoples to shape a cultural identity through resistance, liberation and catharsis” (Nurse 2010, 662). Nurse highlights the ways in which Carnival occurred and existed across the Caribbean diaspora as rebellion and opposition were inherent across all enslaved people in the Caribbean.These rebellions all take a similar shape or form, showing unity within Caribbean culture as well as complexity and nuance in the ways Caribbean culture differs across the islands.

Works Cited:

"Koo, Koo, or Actor-Boy", Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in

the Early African Diaspora. http://slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2309

"Jaw-Bone, or House John-Canoe", Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and

Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora. http://slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2311

Martinez-Ruiz, Barbaro. "Sketches of Memory: Visual Encounters with Africa in Jamaican Culture." In

Art and Emancipation in Jamaica: Isaac Mendes Belisario and His Worlds, edited by Tim

Barringer and Gillian Forrester and Barbaro Martinez-Ruiz. New Haven: Yale Center for British

Art, (2019). https://www-aaeportal-com.ezproxy.neu.edu/?id=-18630.

Nurse, Keith. “Globalization And Trinidad Carnival: Diaspora, Hybridity And Identity In Global

Culture.” Cultural Studies, 13:4 (1999):661-690, DOI:10.1080/095023899335095

Thompson, Robert Farris. "Charters for the Spirit: Afro-Jamaican Music and Art." In Art and

Emancipation in Jamaica: Isaac Mendes Belisario and His Worlds, edited by Tim Barringer and

Gillian Forrester and Barbaro Martinez-Ruiz. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, (2019).

https://www-aaeportal-com.ezproxy.neu.edu/?id=-18629.

Further Readings:

Scher, Philip W. Carnival and the Formation of a Caribbean Transnation. Gainesville:

University Press Of Florida, 2003.