Carnival and Mass

This section looks at the power carnival and masquerade carry as well how it manifests rebellion. One of the ways this section does this is be engaging in masking rituals.

We also see this form of remembrance being carried through the costumes worn and music played during this celebration of freedom. Mask making is very powerful as it suggests that the maker is “transforming themselves” in efforts to connect with ancestors (Liverpool 1998). The act of mask making and masquerade is an African practice and was used to both overcome and fight the system. Connecting with one’s ancestors was done for a multitude of reasons such as remembrance, thanking their acestors for a good harvest, finding a means of escape, or finding guidance when forced into systems of oppression (Liverpool 1998). As Riggio says in“ Play Mas - Play Me, Play We”, “in a culture of multiple identities, to ‘play yuhself,’ as the Carnival cliche suggests, may be best achieved in the fantasies of the so called ‘other. This reality complicates our understanding of Carnival masking in a situation in which ‘dressing up’ and ‘dressing down’ in Carnival season mean more than temporary release or momentary social inversion” (Riggio 1998, 94). Thus portraying the complex nature of masking in Carnival.

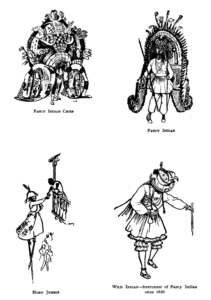

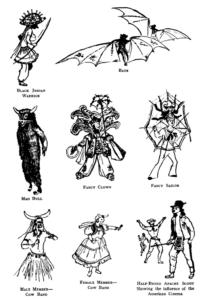

In Williams C. Day’s Five years' residence in the West Indies, Day depicts Carnival as a “negro masquerade”, vividly describing costumes, yet completely failing to acknowledge the meaning, power, and purpose these costumes carried. This is significant because though he is witnessing these events taking place, he doesn’t understand them, merely illustrating the exclusivity and opposition Carnival carries toward colonial culture. Carnival is something the colonizer could never fathom because colonial powers are blinded by the control and superiority colonizers believe they carry. He describes varying costumes mentioned above, such as pirates, the devil, Indians, angels, queens, enslaved people with chains on their necks, etc. Yet he ends his narrative emphasizing his distaste in the music, costumes, and uproar, showing relief in its end. To him, this celebration reassembled something wild and ungodly, creating a sense of discomfort because of his lack of understanding and access to rituals taking place.

Caption: These images are representative of the different characters and costumes of carnival from Daniel J.’s Crowley’s “The Traditional Masques of Carnival”

Citation: Crowley, Daniel J. "The Traditional Masques of Carnival." Caribbean Quarterly 4, no. 3/4 (1956): 194-223. Accessed March 9, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40652635.

Symbolic characters are oftentimes portrayed through various masks played by Africans (Liverpool 1998). Every act and item used (including body paint, markings, crowns, feathers, cowrie shells, etc), carried a specific meaning and was done purposefully (Liverpool 1998). Costumes would include animals, kings, queens, devils, spirits, etc. People used to paint themselves black, wear worn-out clothes, and pour molasses over themselves illustrating sweat and unpaid labor, to represent Jab, Jab, the devil (Riggio 2004). Negre Jardin is another mask representative of field laborers who would typically reenact the ritual of stick fighting illustrating all labor forced upon them (Riggio 2004). These masks go back to the time of pre-emancipation and still exist in the celebration of Carnival today illustrating how the rituals of Carnival are rooted in history, memory, and ancestry.

All this works to highlight the key role masking played in fighting systems of enslavement. Engaging in these masking rituals, created a facade for colonizers, making colonizers believe that enslaved people were being obedient and assuming their cultural beliefs. Whereas in reality enslaved people were using a “mask” as a way of representing hope, empowerment, and as a veil to connect with their own culture. As Thompson highlights, “Jánkúnu honors the ancestors in heaven, hence plumes, beads, and mirrors: (Thompson 2019), highlighting the connection between mask-making and spirituality. Enslaved people dressed up in varying figures to call upon their own ancestors for guidance as well as a way of transforming themselves. The celebration of Jánkúnu highlights the symbolic connection to spirituality mask-making carried as well as how costumes represented the enslaved’s African roots. Masking was used as a means to empower oneself. Today, the same characters are represented in Carnival celebrations across the Caribbean and Caribbean diaspora as a way of remembering the pain and resilience of the West Indian people. These masking rituals are so powerful, regardless of how much time passes, certain rituals or celebrations will always resonate with the true meaning of Carnival and transcend time.

Caption: This is a modern day image of“Jánkúnu mas in Jamaica in 1975.

Citation: “Junkanoo.” Wikipedia, November 30, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Junkanoo.

Works Cited:

Liverpool, Hollis Urban. "Origins of Rituals and Customs in the Trinidad Carnival: African or

European?" TDR, no. 3 (1998): 24-37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1146677.

Liverpool, Hollis. Rituals of Power and Rebellion: the Carnival Tradition in Trinidad and Tobago,

1763-1962. Research Associates School Times, 2001.

Riggio, Milla Cozart. ‘’Play Mass’ - Play Me, Play We’ In Carnival: Culture in Action: the Trinidad

Experience, edited by Riggio, Milla Cozart, 93-108. London: Routledge, 2004.

Riggio, Milla C. "Introduction: Resistance and Identity: Carnival in Trinidad and Tobago." TDR (1988-)

42, no. 3 (1998): 7-23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1146676.

Thompson, Robert Farris. "Charters for the Spirit: Afro-Jamaican Music and Art." In Art and

Emancipation in Jamaica: Isaac Mendes Belisario and His Worlds, edited by Tim Barringer and

Gillian Forrester and Barbaro Martinez-Ruiz. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, (2019).

https://www-aaeportal-com.ezproxy.neu.edu/?id=-18629.

Images Cited:

Crowley, Daniel J. "The Traditional Masques of Carnival." Caribbean Quarterly 4, no. 3/4 (1956):

194-223. Accessed March 9, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40652635.

“Junkanoo.” Wikipedia, November 30, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Junkanoo.

Further Readings

Procope, Bruce. "The Dragon Band or Devil Band." Caribbean Quarterly 4, no. 3/4 (1956): 275-80.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40652641.

Scher, Philip W. "The Devil and the Bed-Wetter: Carnival, Memory, National Culture, and Post-Colonial

Conciousness in Trinidad." Western Folklore 66, no. 1/2 (2007): 107-26. Accessed March 9,

- http://www.jstor.org/stable/25474847.