Carnival and Song

This section speaks to the importance of the relationship between carnival and songs as well as the illustrate the power oral tradition carries. One of the ways this section does this is through its focus on the Caribbean as being a place of cultural power.

Carnival being an oral tradition is a form of resilience in itself. An oral tradition is passed down through generations and is representative of strength, as oral traditions are oftentimes performative, meaning they could be told through songs, dance, and ritual, as well as stories. Strength is shown through the will power and resilience of being able to carry and learn one’s ancestry during colonial attempts of erasure. Oral tradition also defies colonial knowledge-making, which believes knowledge must be written down in order to have value or to be regarded as true. This reliance upon the power of print culture perpetuates the idea that Black indigenous people did not have any sense of record-keeping, because much of their history was carried on through oral tradition, rather than physical remnants. Oral traditions also cannot be destroyed in the way that a physical record can be since oral traditions exist in the collective memory. When an enslaved person is stripped of everything, “oral tradition provided a filter through which the disinformation of the demonized selfhood of black people, as propagated by white slave owners and white authority, often given validity by text, could be countered and challenged” (Reddie 1998, 16). Oral traditions were a way of combating all the false information enslaved people were being told and gave people a means of connecting with themselves, and their own culture.

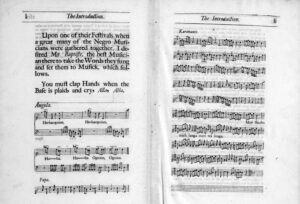

Caption: “Slave Song, Jamaica, 1687-1688” is one of the first Anglo-American records of slave music. This just gives some insight into what slave music may have looked at during this time.

Citation: Hans Sloane, A voyage to the islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, . . . and islands of America. (London, 1707), vol. 1, pp. l-li. (Copy in the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University)

As part of the Cannes Brulees, Canboulay riots, and Carnival today, song plays a huge role. Such songs are shown in Mrs. Carmichael’s journal, though she failed to understand them. Even after Mrs. Carmichael got a young child to explain the song and what it meant, she still failed to understand the song’s meaning. As she says, “the tune to which this is sung, is said to be negro music; it is on a minor key, and singularly resembles an incorrect edition of an old Scotch tune, the name of which I do not recollect” (Carmichael 1779, 302). Everything she saw must be compared to her western life to make sense, diminishing the significance of the rituals taking place right before her, because Mrs. Carmichael failed to see these celebrations as being drawn from African origins.

The ways in which Mrs. Carmichael saw these rituals as being “incorrect” parallels Day’s view — instead of referencing or comparing Carnival to European culture, the Caribbean should be seen as a cultural center that stands on its own. Further emphasizing why we cannot trust the perspective westerners (like Day and Carmichael) write from because of their inclination to compare Carnival to the only thing they know — European culture. How would the perspective change if the Caribbean was viewed as the place of cultural origin? Day and Mrs. Carmichael tells us that carnival is a cheap version of European culture because western travelers are unable to understand and see Carnival for its true meaning and significance as Carnival is representative of a culture they lack access to. So why should we take Day and Mrs. Carmichael’s word at face-value when they lack cultural literacy and knowledge about non-European cultures? The Caribbean exists as a form of both cultural power and currency. If we consider the Caribbean as being a place of cultural power, what can we gather or learn from these western texts?

Thus showing reasons why looking at Mrs. Carmichael’s perspective is important, she oftentimes overlooks what is in front of her or clearly tries to avoid giving power to or crediting anything that is not western in nature. Though her journals prove to be helpful in terms of gaining an idea of the songs being sung, allowing us to grasp a better understanding of Cannes Brulees in general.

Caption: This is an image of Hollis Liverpool, a scholar and Calypso artist in Trinidad and Tobago

Citation: Ali, Azad. “Chalkdust Awarded T&T’s Highest Honor.” Caribbean Life News, September 26, 2019. https://www.caribbeanlifenews.com/chalkdust-awarded-tts-highest-honor/.

As Kim Johnson and Dereck Gay write in “Notes on Pan”: “These diasporic Africans salvaged the shards of tradition and culture and collected anything else they could find in that holocaust, and out of the debris they created a culture that embraces all to collectively celebrate the unique beauty of the present” (Johnson and Gay 1998, 74). These Canboulay songs grew into what is now known as calypso (music that originated in West Africa and was brought to Trinidad by those enslaved). Hollis Liverpool defines Calypso as “a song encompassing all the African cultural traits relating to music: percussive rhythmic beats, the call and response pattern, extemporaneous singing and satire” (Liverpool 2001, 185). Calypso reflects the resilience of African identity as well as illustrated resistance to enslavement and colonialism by carrying roots from days of the Kalinda chants.

Works Cited:

Carmichael, Mrs. (A. C.). Domestic Manners And Social Condition of the White, Coloured, And Negro

Population of the West Indies. 2d ed. London: Whittaker, 1834.

Johnson, Kim, and Derek Gay. "Notes on Pans." TDR, no. 3 (1998): 61-73.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/1146681.

Liverpool, Hollis. Rituals of Power and Rebellion: the Carnival Tradition in Trinidad and Tobago,

1763-1962. Research Associates School Times, 2001.

Reddie, Anthony. “The Oral Tradition of African-Caribbean People as a Resource for Black Christian

Formation”, British Journal of Theological Education, 10:1, (1998) 16-25, DOI:

10.1080/1352741X.1998.11673917

Images Cited:

Ali, Azad. “Chalkdust Awarded T&T’s Highest Honor.” Caribbean Life News, September 26, 2019.

https://www.caribbeanlifenews.com/chalkdust-awarded-tts-highest-honor/.

Hans Sloane, A voyage to the islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, . . . and islands of America. (London,

1707), vol. 1, pp. l-li. (Copy in the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University)

Further Readings

Brathwaite, E. L. "Caribbean Theme: A Calypso." Caribbean Quarterly 4, no. 3/4 (1956): 246-49.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40652638.

Pearse, Andrew. "Mitto Sampson on Calypso Legends of the Nineteenth Century." Caribbean Quarterly

4, no. 3/4 (1956): 250-62. Accessed March 9, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40652639.