Carnival Exhibit Introduction

“African slaves never forgot about where they came from and passed along their memories to each subsequent generation through oral history and reminiscences”

- Dwaine Plaza & Jane DeCosmo, “Women and the De-Africanization of Trinidad Carnival: From the Jamette to Bikinis, Beads, and Feathers”

CARNIVAL

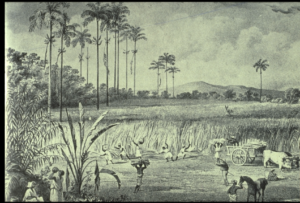

Caribbean Carnival is a festival of freedom performed in the face of European enslavement. The word “Carnival” has roots in the pre-emancipation ritual of Cannes Brulees (sugarcane burning) that occurred on the massive sugar plantations that enslaved thousands of Africans in the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries. Here we explore the rich trove of historical sources that reveal acts of rebellion, music-making, dance, masking, and ritual at the origin of Carnival.

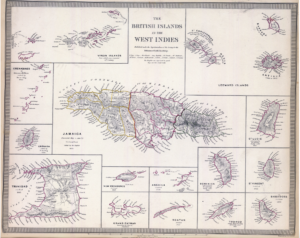

Trinidad and Tobago is ground zero of Carnival’s history. Most of the materials we explore originate there, though texts from other islands in the West Indies included show that Carnival acts of rebellion and performance spread throughout the Caribbean and the Caribbean diaspora.

Caption: British Islands of the West Indies in 1835; Trinidad in lower left; Tobago lower right.

Citation: “1835 Map of Trinidad and Tobago.” Britishempire.co.uk, 2015. https://www.britishempire.co.uk/images2/britishislands1835map.jpg.

Defiant acts of rebellion and power form the core of carnival. But unlike violent revolts and riots, Carnival is a more subtle expression of rebellion. Enslavers tried to separate and divide those they enslaved, aiming to rid enslaved people of individuality or ties to their own culture. Yet oral traditions and celebrations (like those practiced in Carnival) allowed enslaved people to resist this attempt at division by actively performing ties to their roots. Carnival performance rebelled against the dehumanizing violence of slavery.

Carnival celebrates culture and freedom created for, and by, Caribbean people. The rituals, masking, song, and dance of Carnival are all part of Afro-Caribbean culture, a culture colonizers lacked the insider knowledge necessary to fully understand or participate in. Carnival allowed enslaved people to perform their opposition to colonial power through the extravagant, public refusal to unlearn or suppress their own culture. Colonizers wanted the enslaved to forget or neglect their own beliefs, in order to immerse themselves in a western culture that devalued Black humanity, as a way of disconnecting enslaved people from any life beyond enslavement.

Caption:“Sugar Cane Harvest, Trinidad, 1836.”

Citation: "Sugar Cane Harvest, Trinidad, 1836", Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, accessed March 9, 2021, http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1112

Carnival not only excluded colonizers and refused their authority, it also mocked colonizers’ claims to understanding the world of enslaved people. Carnival rituals or celebrations performed right in front of colonizers demonstrated that they were unable to understand the essence or significance of these celebrations and enabled West Indians to mock the ignorance of these so-called “superiors.” As the historian J.D. Elder writes, “only the Africans are enabled to understand the ‘message’ because the very medium IS the message” (Elder 1998, 38). A large part of the rebellious nature of Carnival lies in its resistance to and impenetrability to colonial knowledge. Colonizers’ lack of understanding of Carnival reveals their absence of cultural literacy with respect to Afro-Caribbean culture. Afro-Caribbean culture is dynamic and complex, filled with traditions, rituals, and ways of life that are impossible for colonial forms of knowledge, (which deem it worthless), to grasp.

Works Cited:

Elder, J. D. "Cannes Brûlées." TDR, no. 3 (1998): 38-43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1146678.

Kincaid, Jamaica. A Small Place. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2000.

Images Cited:

“1835 Map of Trinidad and Tobago.” Britishempire.co.uk, 2015.

https://www.britishempire.co.uk/images2/britishislands1835map.jpg.

"Sugar Cane Harvest, Trinidad, 1836", Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade

and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, accessed March 9, 2021,