Where Does Obeah Come From?

"Obeah is clearly an African Religious art and practice that survived through colonial Caribbean culture."

—Nathaniel Samuel Murrell

in Afro-Caribbean Religions: An Introduction to Their Historical, Cultural & Sacred Traditions

Where can we trace the practice back to in Africa?

Obeah originates from native West African religions but can claim roots in almost anywhere or anything. Practice can be traced back to the enslaved and the Maroons of Jamaica, but its practice extends throughout the Caribbean in places like Guyana (where Indian influence is most present) and through Latin America and South America.Just like the people and language of the Caribbean, the practice is unique to its place, as the result of mixing cultures and circumstances due to colonization. While Obeah is not uniform or universal in its practice, it is inclusive. Because of the endless iterations of cultures, ethnicities, and colonizers coming together, all with different roots and belief systems, it would be nearly impossible to have uniformity in any way within the Obeah community. Instead, it sought out acceptance of all practices of Obeah.

With multiple sects and origins coming together, it created what philosopher and historian of religion Nathaniel Samuel Murrell called a cultural “symbiosis.” Many colonized people from different backgrounds were able to interact and relate through shared common beliefs and culture. Thus resulting in greater harmony and a sense of solidarity against colonizer rule.

How might maps and visualizations help us better understand?

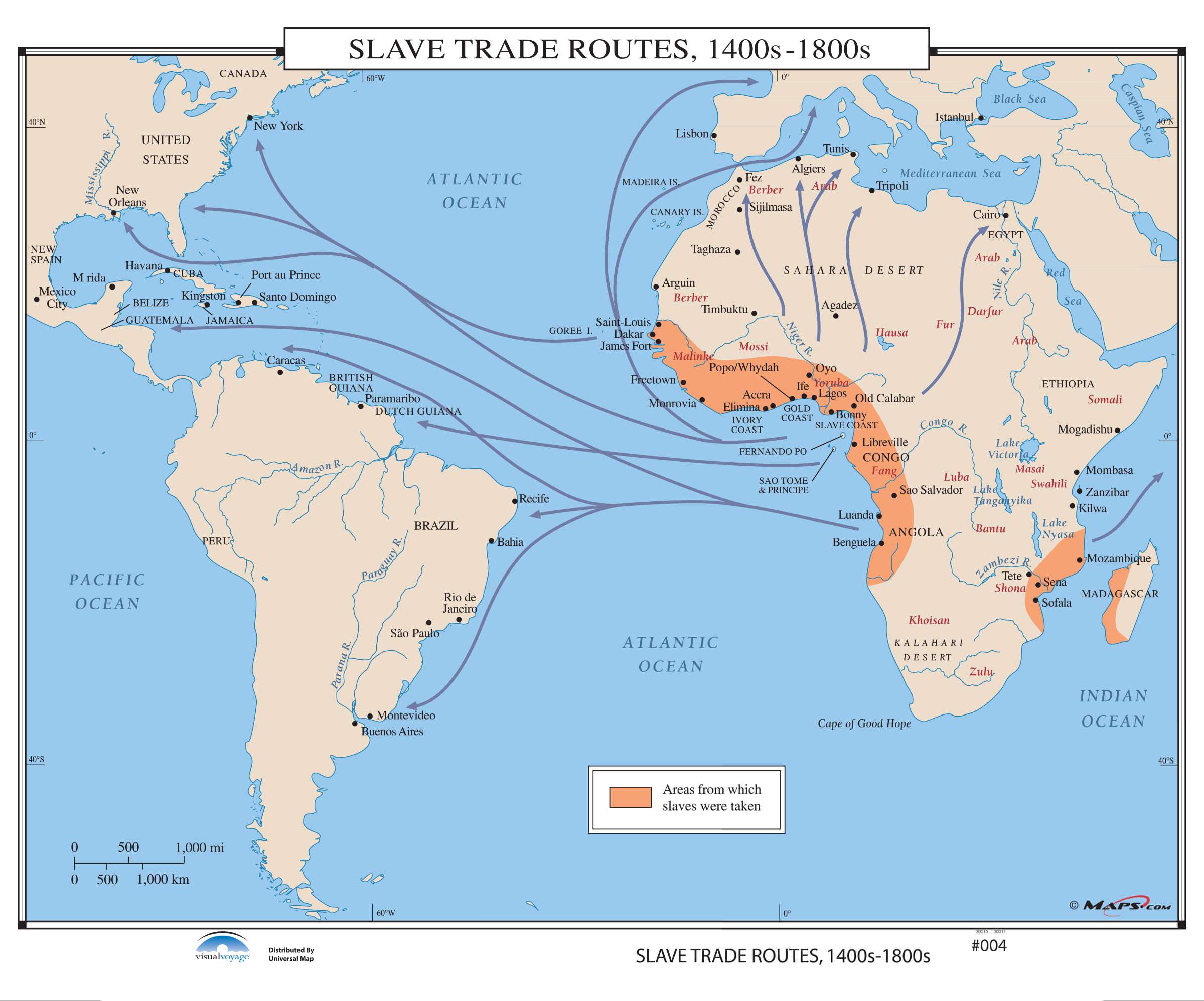

This map shows the routes of the slave trade as Africans were enslaved and sent to the Americas, it gives us insight into how cultures and practices combined as Africans from across the continent met with one another and the indigenous people that were living in the Americas. Understanding the religion and practices at the origins and where they were sent to might give us insight into what manifested as they came together.

In this way, maps can be incredibly helpful in understanding how people traveled across the Atlantic and arrived in the Caribbean. Still, what is critical to remember is that the movement was never final, and many people including the colonists, free Black people, and enslaved people, continued to travel across the Caribbean and the rest Americas after reaching their original destination. With that, practices, religions, and cultures changed and continued to influence one another in limitless permutations. This undoubtedly influenced how Obeah was shaped and how it was taken up. For us, it becomes clear that given the nature of the archive more broadly it might be hard to definitively trace influences in their entirety and accurately; however, maps and other archival artifacts might continue to help point us in the right direction. Using digital tools and what Saidaya Hartmann coined as "critical fabulation" in her work "Venus in Two Acts" (published in Small Axe) we can begin to imagine how Obeah came to be in the Caribbean.

What are the alternatives to maps and the archive in discovering Obeah's origins?

A sometimes overlooked resource are the oral histories, local knowledges, and other knowledge forms known by today's Caribbean people. Many of them know their ancestor's lives and stories that have been passed down, giving a more specific understanding of the practices of Obeah in the early Caribbean. Not only does this give us a sense of how Obeah came to form (and from where), but it also gives us a better sense of how it was a part of the everyday lives of the practitioners, and how individuals made the religion their own. This further opens avenues for understanding how Obeah proliferated across the Caribbean.

In undertaking this research with these live subjects, it is important to be careful of how one classifies and contextualizes it— in order to avoid replicating the horrors of colonial knowledge extraction from the Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people in the Caribbean,it is important to give proper credit to the speaker and to regard their stories not just as 'hearsay' or otherwise, but to treat it as valid, intellectual, and valuable information. Although we cannot undo what has already been done, taking up decolonial practices and methodologies in one's pushes us into a better direction, and ensures a more positive future for the study.